There are so many important historical sites – heroic events – moving stories in the world linked to 1914-1918. We have gathered a few (which is not an exhausted list of course) located in Southern Belgium that we would like to share with you.

The Liège Forts

The dubious distinction of being the city where hostilities began belongs to Liège, which lay directly in Germany’s ‘invasion corridor’ to the inadequately defended section of the French frontline. Having declared war on France on 3 August 1914, the Kaiser ordered his troops to march across the Belgian border the following day, drawing Britain into the hostilities because Belgium’s neutrality had been violated. The Germans’ first objective was neutralising the key industrial city of Liège. They thought the task would be straightforward, but they were wrong. Belgium might have lacked Germany’s military muscle, but its courageous resistance was crucial in giving Britain time to move an expeditionary force across the Channel.

A quarter of a century earlier, Belgium had prepared for a future invasion by constructing a dozen concrete forts in a belt around Liège, equipped with their own generators, telephone and air conditioning systems, and fortified with German-made guns. But by August 1914, the forts were no longer fit for purpose. The unreinforced concrete was not strong enough to resist the Germans’ heavy artillery, including their new supergun, the ‘Big Bertha’ howitzer

Loncin Fort

The place where this oversight was most tragically exposed was Fort de Loncin, 7km north-west of Liège. It was built in 1888, when the designers had no idea how quickly armament technology would advance. After withstanding a three-day bombardment, one of the fort’s magazines, containing 12,000kg of gunpowder, was struck by a shell from Big Bertha at 5:20pm on 15 August 1914. The main structure collapsed in apocalyptic fashion. Its interior fabric was torn apart, and its heavy guns shattered and dispersed like petals blown from a flower. Three hundred and fifty of the 550-strong garrison were killed instantly or buried alive. Big Bertha fired 420mm shells weighing 800kg with a range of about six miles. The gun became widely celebrated in Germany, and its bulls-eye at Fort de Loncin was used as a powerful propaganda tool. The bodies recovered from the rubble are buried in a crypt, but more than 100 were never found, and the site is now a military cemetery as well as a ‘living museum.’

Today, much of the damaged masonry and gun emplacements have been left just as they were. One 40-tonne gun lies on its back, having been tossed into the air like a pancake. Massive gun turrets lean at crazy angles. Whole sections of the fortified wall were displaced, with the cracks and fissures plain to see, exposing the inadequacy of the concrete used to bind the structure together. Even today, with grass and flowers softening the scene, the extent of the devastation is chilling.

Some of the fort is unsafe for visitors, but there’s plenty to see. There are waxwork displays showing what life was like for the soldiers – a bakery, butcher’s and kitchen have been re-created to depict everyday life for the underground defenders. Every few minutes, loudspeakers recreate the sound of the ear-piercing explosions. Nearly a century later, Fort de Loncin triggers extremes of emotion. Among its many artistic monuments to the dead is the flamme du souvenir, the figure of a male torso thrusting a torch into daylight from beneath the earth.

Siege of Namur

As at Liège, Namur had been fortified between 1888 and 1892 with the construction of a ring of nine forts around the town to defend the Sambre and Meuse Rivers. The forts were linked by trenches, protected by barbed wire. With the fall of Liège the German Second and Third Armies turned their attention to Namur. Resistance was never going to be prolonged. The garrison was low on morale, ammunition and, most critically, manpower. At its best Namur was garrisoned with approximately 37,000 men, against at least 107,000 German troops.

Namur intended to hold out until the arrival of French Fifth Army forces stationed across the River Sambre to the south-west. But the French were diverted away from the forts by other German incisions, and only one regiment was able to help with Namur’s defence. The citadel, thought to be impregnable, was captured after three days’ fighting, and as at Liège, the Germans successfully bombarded the forts with heavy artillery. By 23 August 2014, five of the nine forts lay in ruins and Namur was close to collapse. At midnight, the garrison withdrew from the town to link up with the remainder of the Belgian army, and the last fort surrendered on 25 August.

Inter-Allied Memorial

Liège, the first city to have stood up with success to the invaders in 1914, was chosen in 1925 by the International Federation of Allied Ex-Servicemen for a memorial. The monument, both civil and religious, is a tribute from the allies of the 1914-18 war to the heroic resistance of Liège and Belgium.

Dinant and the ‘Martyr Towns’

In the opening weeks of World War One, as the strong German army raced alongside the River Meuse in an attempt to outflank the French Army, its troops carried out a series of atrocities against civilians who were not in a position to defend themselves. An official report written during the war by Brand Whitlock, the US Minister to Belgium, detailed some of the atrocities that occurred in August 1914: “Over all this … rich agricultural region dotted with innumerable towns, villages and hamlets, a land of contented peace and plenty … there were inflicted on the civilian population by the hordes that overran it deeds of such ruthless cruelty and unspeakable outrage that one must search history in vain for others like them committed on such a prodigious scale. Towns were sacked and burned, homes were pillaged; in many places men, women and children were massed in public squares and mown down … and there were countless individual instances of an amazing and shameless brutality.”

Dinant paid the heaviest price. Suspected to be the base of Belgium’s guerrilla force, the town was torched and the population decimated. In one incident, soldiers fired indiscriminately into a crowd that included mothers with babies; in another, 150 factory workers were ordered outside and summarily executed. In all, 674 townsfolk died. Dinant was totally rebuilt after the war, including the distinctive onion-domed Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame, but memories took generations to fade. It was not until 2001 that the town gave permission for the German flag to be flown alongside the other EU national flags on the bridge across the Meuse.

Eight other towns and villages belong to the so-called ‘Villes Martyr’. At Porcheresse in the Ardennes, the entire population was herded into the village church and burned alive. Visé, on the Dutch border, was mostly burnt: nearly 600 houses were destroyed. Tamines was transformed into a mass of ruins and 383 civilians were executed. A large monument in the village honours the ‘martyrs’. Nearby Sambreville saw the massacre of 384 townspeople, including women and children, and another 200 people were slaughtered at Andennes, on the Meuse between Liège and Namur.

Battle of the Frontiers

It was made up of four separate battles including the Battle of the Ardennes (20-25 August), the Battle of the Sambre also known as the Battle of Charleroi (22-23 August) and the Battle of Mons (23 August). It marks the period when the German armies advancing through Belgium emerged at the French borders and began to force the French to retreat back.

The battle was fought on a massive scale. Both the French and Germans committed well over 1,000,000 men, in five French and seven German armies.

Battle of Mons : The First and Last for the Allies

Within days of disembarking in France, the hurriedly-organised British Expeditionary Force of 70,000 men marched northwards and engaged the Germans near the Mons Canal in an effort to protect the left flank of the retreating French army. On 23 August 1914, outnumbered two to one and described by a German general as ‘a contemptible little army’, the British fought their first battle on European soil since Waterloo.

For 48 hours ‘The Contemptibles’ held the line, losing 1,600 men but inflicting heavier casualties on the enemy. But defeat was inevitable. Some of the fiercest fighting took place at the Nimy railway bridge, where the first Victoria Crosses were awarded to two British machine-gunners of the 4th Royal Fusiliers, who covered the retreat until they were too badly wounded to continue. One was Lieutenant M. Dease who, although already wounded, took over one of the battalion’s two machine guns to halt the German offensive. He was wounded again and died the next day. The second award was to Private S. Godley. Despite being wounded in the head and back, he took over the other gun and tenaciously fought off the enemy attack, and by doing so gained vital time to allow the withdrawal of the 4th Royal Fusiliers. The legendary Retreat from Mons had begun and the town would not be liberated until the final day of the war, more than four years later

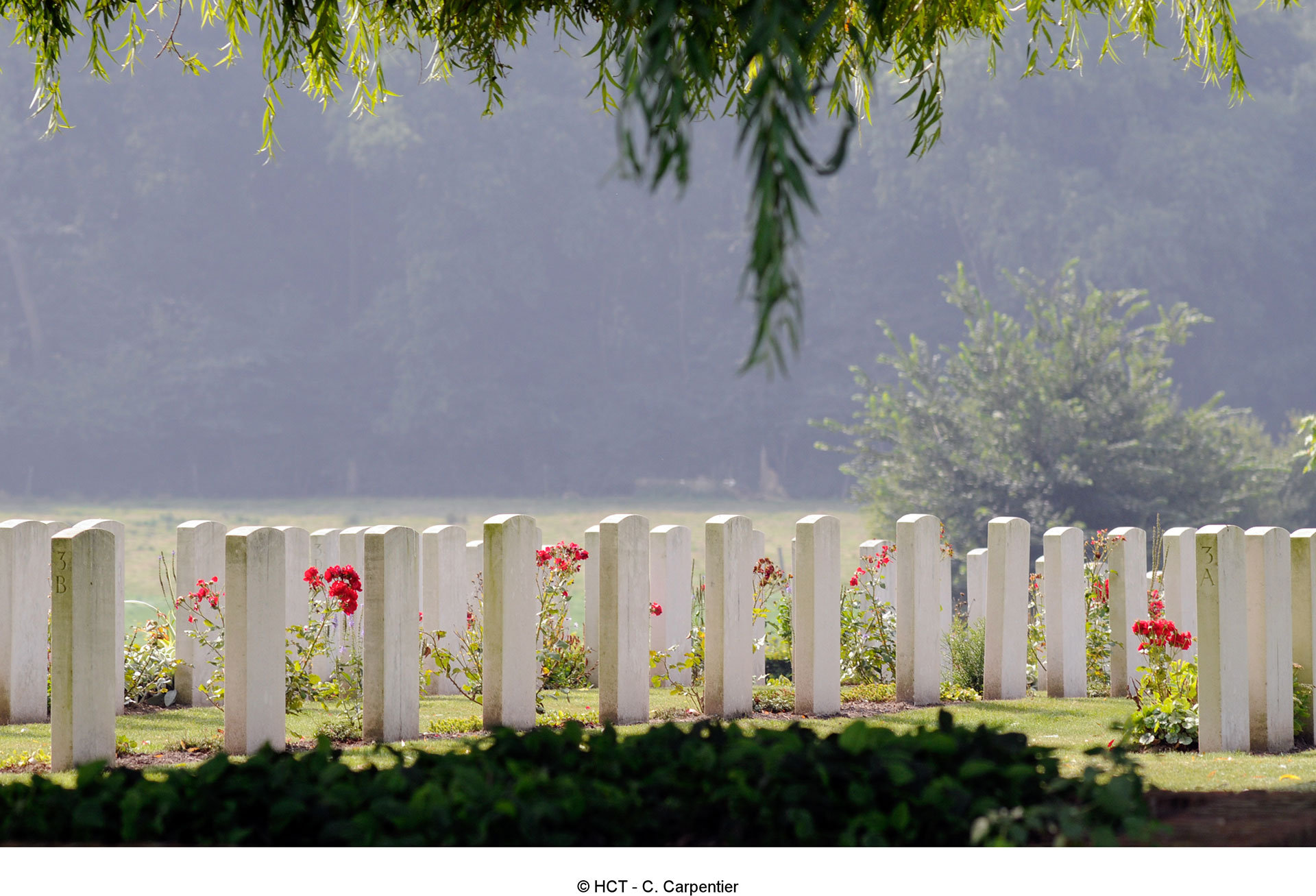

St Symphorien Military Cemetery (CWGC)

This is perhaps the most beautiful and evocative war cemetery in Belgium, unusually containing both Commonwealth and German graves, discreetly separated from each other but united in repose.

It is also where lie the remains of the first and last British casualties of the war. The first was 20-year-old Private John Parr of the Middlesex Regiment, a member of a bicycle reconnaissance team who was killed at Obourg near Mons on 21 August 1914. The last was Private George Ellison of the Royal Irish Lancers, who was killed an hour and a half before the Armistice was signalled. It is also the resting place of Private George Lawrence Price, a 25-year-old farm labourer from Canada who was struck by a single shot and killed two minutes before the 11 a.m. armistice went into effect.

This peaceful and pretty burial site - unusual in being divided into British and German sections - is the final resting place of more than 500 servicemen, including 230 British and 60 who remain unidentified.

On the outskirts of Mons, a small communal cemetery in the village of Nouvelles contains a microcosm of World War I from the British perspective. There are nine white headstones. Five of the graves were dug at the start of the war, in August 1914. The remaining four stones, arranged in line, mark the graves of a soldier from each of England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales – all of whom died on Armistice Day.

Mons Memorial Museum

In the spring of 2015 the town opened its Memorial Museum (MMM), displaying about 5,000 artefacts from the two World Wars, many of them donated by veterans and Belgian citizens. The museum aims to personalise the war experience, focusing as much on the men who wielded the weapons as the weapons themselves. There are pieces of a soldier’s bread ration, preserved in a bottle; Field Marshall Montgomery’s beret, which he presented to Mons when he was proclaimed a Citizen of Honour in 1946; and a German one-tonne bomb – the first in the world, manufactured in 1917.

More intimately, there are numerous recorded interviews with veterans, and a large collection of their diaries, postcards and letters to sweethearts back home.

‘Plugstreet’

Plugstreet (real name Ploegsteert) is the most westerly settlement in Wallonia, just 2km north of the French border. Both found themselves on or near the front line in the early months of the Great War. In Comines, the only relic of the German occupation is a blockhaus, or bunker, which has been well preserved and contains a small museum. Ploegsteert Wood was the site of especially fierce fighting, as the ranks of war graves in the area attest. A notable British connection with Ploegsteert is the fact that Winston Churchill was billeted there between January and May 1916 when he was commanding officer of the 6th Batallion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. There’s a commemorative plate on a wall of the house where he stayed.

Experience Plugstreet 14-18

Pyramid-shaped museum with a cinema showing the background to the Great War, a three-dimensional map of the western front and a special presentation on the battle of Messines Ridge in June 1917, which was won by the Allies when thousands of tonnes of high explosive were detonated beneath the German line. It’s said that the shockwaves carried across the Channel and were felt in London.

Military Cemeteries and The Memorial to the Missing

There are more than a dozen cemeteries and memorials in and around Plugstreet – two of them especially significant – and many are named after places in London and the Home Counties. One of the largest is the Strand Military Cemetery, just north of the village, containing more than 1,000 burials. A little further north is Hyde Park Corner (Royal Berkshire) Cemetery, which was extended across the road in 1916 and, along with 876 named stones, contains the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing, dedicated to those who lost their lives between Warneton and Estines, but whose bodies were never recovered. This graceful circular structure, flanked by two large stone lions, opened in 1931. The marble is engraved with the names of the ‘11,447 officers and men of the forces of the British Empire whose names are here recorded but to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death.’ These men are certainly not forgotten: on the first Friday of every month the Last Post is sounded at 7pm.